‘Hey, Aren’t You Kevin Reilly?’ Ex-Eagle With Local Roots Tells His ‘Two-In-A-Million’ Story

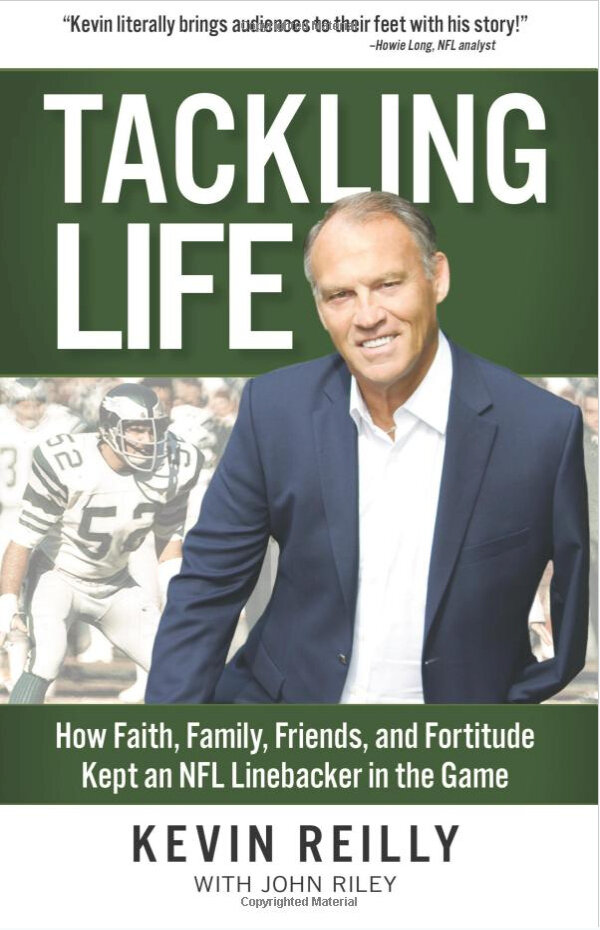

Kevin Reilly poses with his autobiography.

Kevin Reilly could feel the stare as he walked arm-in-arm with his wife along the Stone Harbor beach near 84th Street. He can always feel the stare. He always will.

“The guy is looking and eventually, he says, ‘Hey, aren’t you Kevin Reilly?’ ” Reilly says, before laughing. “I say what I usually say: ‘How many one-armed guys do you know?’ ”

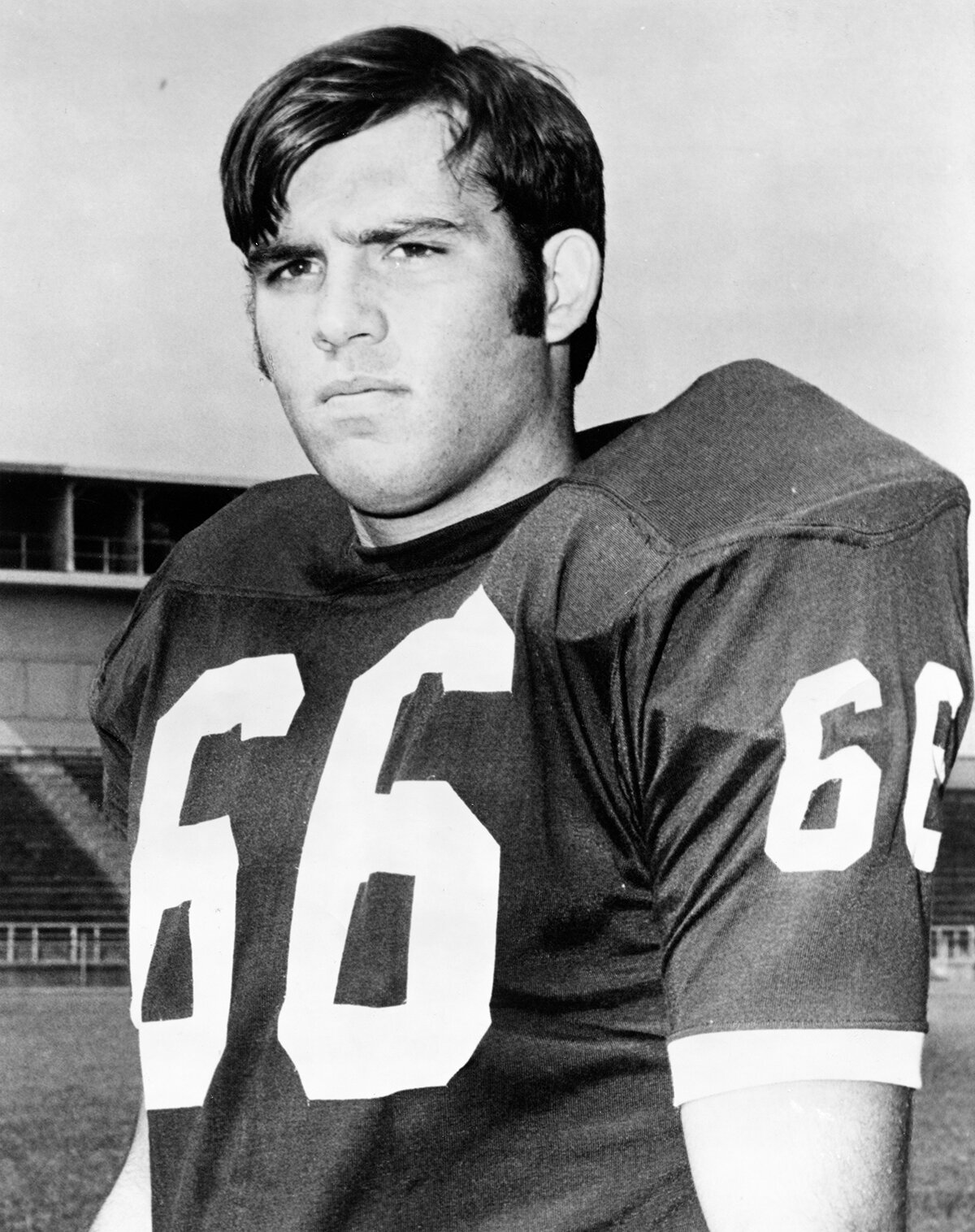

With that, there were smiles, and Reilly would continue his stroll by the ocean, where he’d found so many comforts since he was 6 years old. He’s 67 now. And he has been without his left arm since he was 29, the convoluted result of injuries from playing linebacker for Villanova, the Eagles and the New England Patriots compounded by a “two-in-a-million” genetic misfortune.

His story is captured in his easy-to-read autobiography, “Tackling Life: How Faith, Family, Friends, and Fortitude Kept an NFL Linebacker in the Game,” published last October. His tale of high achievement, painful loss and competitive spirit makes him a busy motivational speaker.

It was on the 90th Street beach in Stone Harbor where his life took an unfortunate turn.

“I was with my dad on Memorial Day,” Reilly says. “And he casually said, ‘What is that?’ ”

There was a noticeable bump between Reilly’s left shoulder and left pectoral muscles, something he was certain was calcium buildup or some other result of two-a-day training-camp practices or the obligation to tackle the likes of Larry Csonka at full speed through his three seasons in the NFL. But it was not going away. Reilly’s father, Fran, suggested a deeper investigation. Neither knew how deep it would go.

At that time, 1976, Reilly had been semi-retired from the NFL yet was hoping to make one more run at pro football. Nine doctors later, all he remembered tackling was pain, excruciating and persistent. Most had correctly diagnosed him with a tumor that, while cancerous, was not spreading to other parts of his body. Still, no matter how it was treated or attempted to be surgically removed, it would return, larger and nastier each time. A 10th specialist, Dr. Ralph Marcove of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, finally made the accurate read. Reilly had a desmoid tumor.

Says Reilly: “I remember him saying, ‘Kevin, we will be lucky if we can save your life.’ ”

Desmoid tumors develop around tendons and organs, endeavoring to naturally protect disturbed areas. Only one in every 500,000 people has the gene to generate one. Reilly, whose rotator cuffs had been traumatized by years of collisions, was not one of the more fortunate 499,999. So, the tumor grew. And whenever it was removed, it would grow back. Again and again, as relentless as ocean waves. Eventually, a desmoid tumor can expand and strangle blood vessels. From there, organs might become threatened. For Reilly, that meant intolerable pain. A more aggressive operation was his only escape.

By then, the situation was so dire that he needed a forequarter amputation. He was told it would cost him his left arm, shoulder and four ribs. “I was in so much pain,” Reilly recalls. “I said, ‘Let’s do it.’ ”

The surgery took 11½ hours and required a complete blood transfusion. Reilly didn’t know it at the time, but at least 11 former teammates from the Eagles, Villanova and Salesianum School in Wilmington, Del., had donated blood for the operation. As for the length of the emotional recovery, that largely would be up to him. By then, though, he had already found peace in knowing it was not his fault.

“I was pushed with the Dolphins and with the Eagles to take steroids because of my weight, and I won’t mention names,” Reilly says. “I don’t know why, but I never took steroids when I was weightlifting, I saw what it did to other guys. I saw how grouchy they got. It didn’t seem natural to me.

“I remember being in the hospital and thinking, ‘At least I can’t blame myself. This is a two-in-a-million thing.’ If I had taken steroids, I would have blamed the tumor on that. And that gave me a lack of guilt that really helped me come out of this thing and say, ‘What can I do to recover?’ ”

That recovery was aided by a phone call from Rocky Bleier, a running back who suffered serious leg and foot injuries during a battle in Vietnam, was told he’d never play football again, then became a pillar on four Pittsburgh Steelers Super Bowl teams. Reilly will never forget Bleier’s response when he told him that some experts on amputation said it would be difficult: “Experts built the Titanic. Amateurs built the ark. Experts can be wrong.”

Reilly recovered quickly and returned to his job in Delaware with Xerox, where he’d been hired after football by fellow Villanova grad Dick Keely. By then a father of a son, Brett, and daughters Erin and Brie, none over the age of 4, he’d vowed to someday coach their athletic teams.

Always, he’d return to Stone Harbor, where his parents, Fran and Kay, rented a home near 83rd Street when Reilly was a youth, and where they still own a condo near 92nd Street. Reilly, who once owned a home in Avalon, still summers at the family condo. His sisters, Kerry Wendel and Megan Gorelick, are members of the Yacht Club of Stone Harbor, where his book is available, and where he will do a July 8 signing at 11 a.m. Already scheduled for a second printing, the book is also for sale at the Stone Harbor Book Shop on 96th Street.

Having been captivated by a mandatory speaking course he’d taken at Villanova, Reilly would accept a part-time job talking football with legendary Delaware sportscaster Bill Pheiffer on WDEL-AM in Wilmington. He was a natural. That led to a regular Monday football show from a bar in North Wilmington, where, on one show, broadcast partners Bill Bergey and Frank LeMaster surprised him with a Christmas gift: The Clapper. They found it funny. Reilly found it funnier.

Eventually, Reilly would move to WIP/WYSP, where he would host pregame and postgame shows for Eagles games. Retired, he still does color analysis for Villanova football radio broadcasts and high school football games televised by Comcast in Delaware. He regularly plays golf. He once completed the Marine Corps Marathon. He is happily married to his second wife, Paula McDermott, a marketing executive at 6ABC whom he’d met through his sisters’ sly urging in Stone Harbor. Among his favorite stunts is to tie his tie while in the process of making his many inspirational speeches.

“But you know what really I miss?” said the grandfather of 10. “I miss being able to hug my grandkids with two arms.”

He hasn’t missed much, however. Instead, Kevin Reilly tackled life. And in the past year, he enjoyed watching his former team win the Super Bowl and his alma mater earn the NCAA basketball championship.

“Not only that, but my book is selling out,” he said, with a laugh. “It’s been a good streak. Hey? Do you want to go to Atlantic City? Let’s go.”