A Lifetime, A Legacy: Frank D’Elia A WWII Hero, Stone Harbor’s Favorite Centenarian

Frank D’Elia

Imagine living through the Roaring Twenties, the Depression, World War II, the post-World War II economic and baby boom, the counterculture era in the 1960s and 1970s, the Civil Rights movement, the first moon landing, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, 9/11 and more.

Stone Harbor’s Frank D’Elia, who died on Dec. 9, 2019 at the age of 100, didn’t need to imagine those historic moments in time. He lived through them.

D’Elia – a member of Stone Harbor’s American Legion Post 331 whose milestone birthday on Nov. 11 was celebrated with everyone in town that Veterans Day of 2019 – did far more than live through World War II. This centenarian survived the Normandy invasion and the Battle of the Bulge, says American League Post 331 Commander Tom McCullough.

In his role as a tank mechanic and commander, D’Elia’s division landed on Omaha Beach in Normandy when the Allies attacked the Germans on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

“It was a first-day landing, sixth landing craft in,” McCullough notes.

Like many vets who have been in war zones, D’Elia kept his combat experiences to himself, the post commander adds.

“Frank went straight to heaven because he landed in hell on Omaha Beach,” McCullough says before describing the deep-red shallow waters that quickly developed at “Bloody Omaha.”

Post 331 members held D’Elia in high esteem, says McCullough: “All members had to hear about Frank was ‘First-day landing at Omaha Beach.’”

To put that into proper perspective, here’s what History.com reports:

At Omaha Beach, bombing runs had failed to take out heavily fortified Nazi artillery positions. The first waves of American fighters were cut down in droves by German machine gun fire as they scrambled across the mine-riddled beach. But U.S. forces persisted through the day-long slog, pushing forward to a fortified seawall and then up steep bluffs to take out the Nazi artillery posts by nightfall. All told, around 2,400 American troops were killed, wounded or unaccounted for after the fighting at Omaha Beach.

Less than seven months later, D’Elia was on the ground in Ardennes, Belgium, for six frigid weeks in late 1944 and early 1945 during the Battle of the Bulge. The Battle of the Bulge was fought during the coldest winter in that region, McCullough explains. That’s how D’Elia and the soldiers who fought during this campaign spent their Christmas and New Year’s, he muses.

D’Elia was awarded a Bronze Star for heroism in combat, a Distinguished Service medal and a Good Conduct medal for his efforts in defeating Nazi Germany.

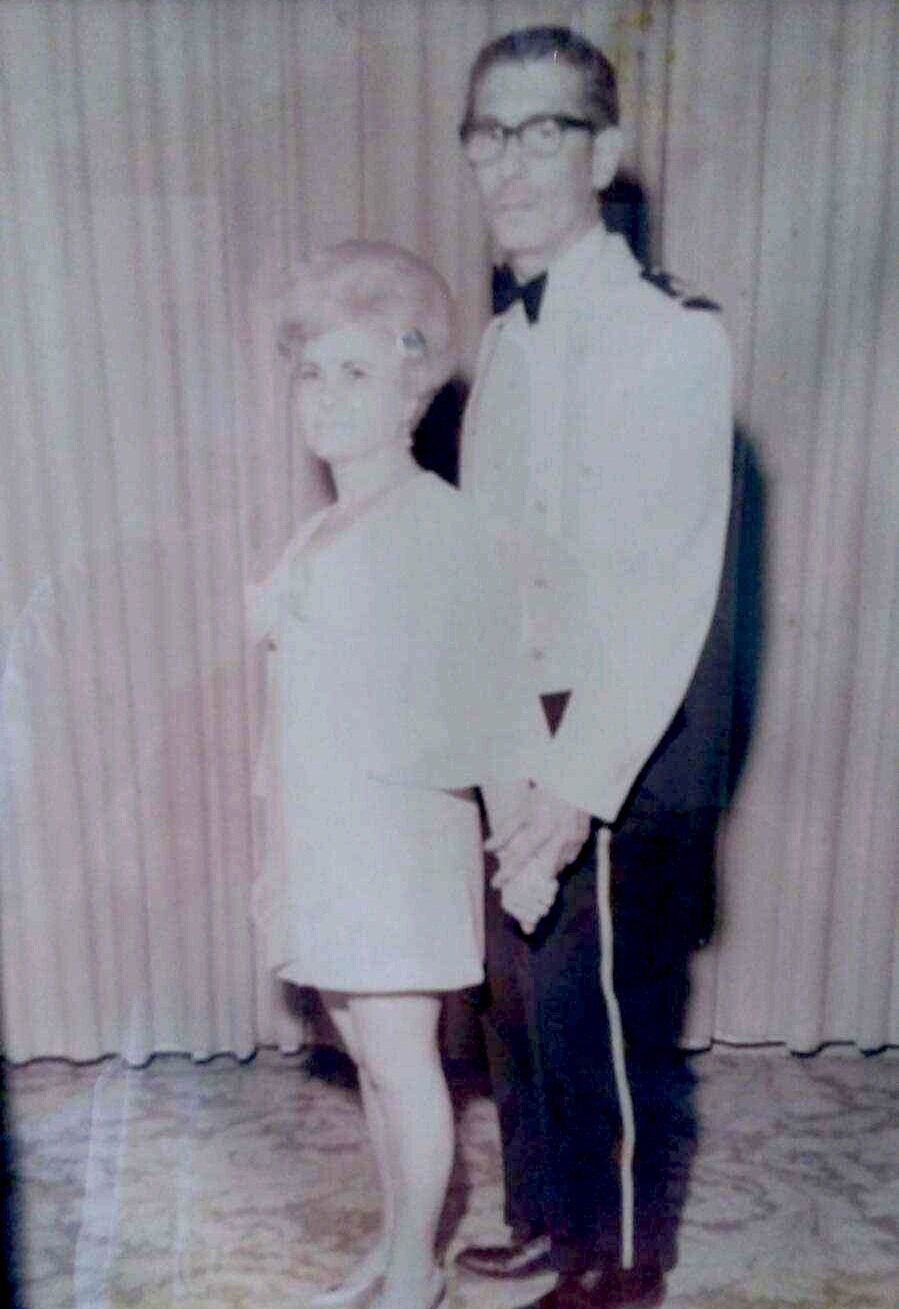

Shortly after World War II, D’Elia met and fell in love with Pauline Cocchi at Veterans Hospital in Philadelphia. The couple married and D’Elia opened his carpentry business in West Philadelphia. Born and raised in South Philly, D’Elia first came to Stone Harbor with his parents, Gaetano and Chiarina, as a 1-year-old in 1920. The D’Elia family home on 81st Street served them well until the brutal nor’easter storm of 1962 obliterated it.

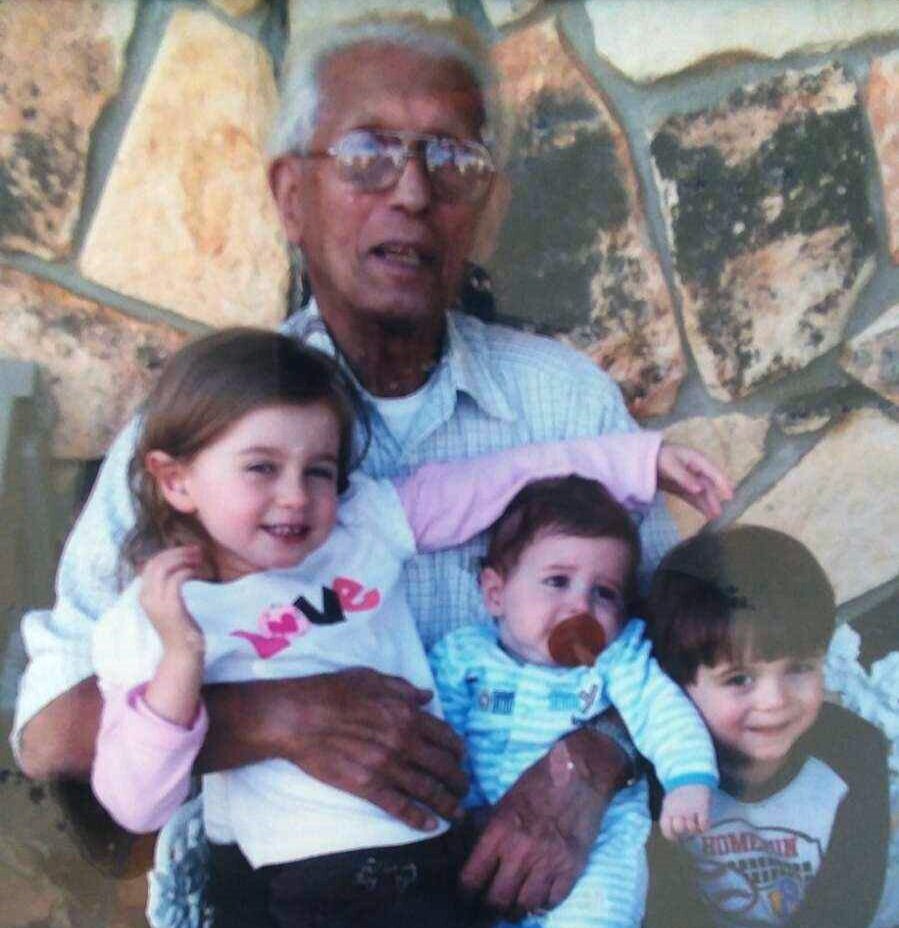

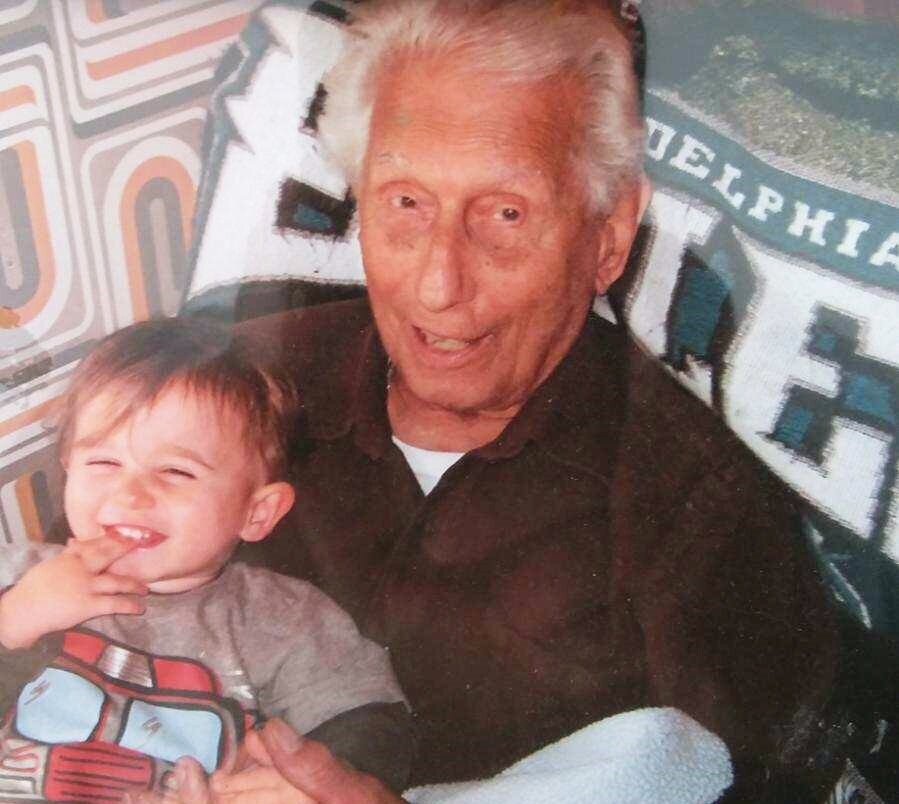

D’Elia and his spouse purchased a house and made Stone Harbor their permanent home in 1977. Pauline passed away in 2003. The D’Elias are survived by their daughter, Pauline D’Elia Tate, and her husband, EJ; daughter Kathy Williams and her husband Bruce; grandchildren Anthony Brullo and Nicole Difiore, and five great-grandchildren.

EJ Tate remembers his father-in-law as “a family man who would rather watch the Mummers Parade than the Super Bowl.” D’Elia also enjoyed cigars and wearing good-looking, properly crafted men’s suits. His father, Gaetano, was a tailor, Tate explains.

When Tate accompanied D’Elia to join more than 83,000 people in seeing then Pope (now Saint) John Paul II at Giants Stadium in October 1995, D’Elia thought it best that they wear suits. “It was pouring rain” that day, says EJ. Two nuns gave Frank and EJ trash bags to wear over their suits, along with a bag of grapes, he adds. He recalls fondly, “Frank ditched his trash bag because it did not match his suit!”

Tate’s suit was still wet the next day when he joined D’Elia for the first of many annual retreats they would attend together at the San Alphonso Retreat House in Long Branch. Once again, D’Elia insisted that they wear suits to the retreat, Tate notes. When they arrived and Tate found everyone wearing T-shirts and shirts, D’Elia said playfully, “I got you!”

By all accounts, Frank’s home away from home was St. Paul Church (now part of St. Brendan the Navigator Parish) at 99th Street and Third Avenue in Stone Harbor.

Retired pastor Msgr. Liam Quinn remembers his initial meeting with D’Elia “in the dark of the morning” on the priest’s first day at St. Paul. As the clergyman returned from an eventful walk with his two Jack Russell Terriers who had just met a skunk, Quinn spotted “sparks flying” near the church in the distance. The sparks flew from cigars being smoked by D’Elia and his good buddy, Frank Bozzi. The pair were there to open the church and prepare for early-morning Mass, the then-new pastor soon learned.

“Frank was a very hard worker, good with his head and good with his hands,” Quinn says. “He liked to be in charge; he was a take-charge sort of guy … in a nice way.” Thus, D’Elia became “the go-to man” at St. Paul Church and “the boss around the altar,” Quinn adds.

These strong tendencies to lead became a source of levity between the pastor and his most active parishioner. At one point, Quinn joked with D’Elia that he would make him “an honorary president for life” of the parish council. “Later, I christened him ‘The Cardinal in Pectore,’” recalls the priest before explaining the term in which a pope secretly names a cardinal who is “a cardinal in the heart.” The nickname stuck. D’Elia, who wore a special cassock when he acted as an altar server during Mass, became widely known as “The Cardinal.”

D’Elia devoted himself to the church and the Blessed Sacrament, Quinn notes. For 63 years, this dedicated parishioner was also a member of the Knights of Columbus, a Catholic men’s group committed to altruism in the United States and globally. “The Cardinal” was well-liked by year-round and summer residents and visitors, the former pastor adds.

“Frank was unusual,” Quinn muses. “His likes won’t be seen again!”

Still, his good works linger.

Tate, who sometimes worked alongside his father-in-law, recalls a few of the faith-based projects that D’Elia constructed or implemented that are now part of St. Paul.

“We built the crying room and the shrine below the crying room,” Tate says of the glass-enclosed balcony reserved for families with young children and the shrine that was originally dedicated to the Blessed Mother. Both sit tucked neatly to the right of St. Paul’s main altar.

His father-in-law also “spearheaded” the effort to convert a garage into Quinn Hall, which has served as a meeting place for all sorts of church gatherings since 2006, Tate adds. Not only that, D’Elia created the setting and managed the installation of the handsome St. Paul sculpture that sits outside the church to the left of the building.

“Frank built all of that by himself,” Tate says.

The St. Paul statue gazes upward as he appears to stride across the church’s front lawn. Words from the saint grace a plaque below the statue. It reads: “I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith and now the prize – Eternal Life” (2 Timothy 4:7).

Fitting words to live and die by … as Frank D’Elia knew well.