Doom With A View: A Look Back At Avalon’s Star-Crossed Hotel Peermont

Hotel Peermont

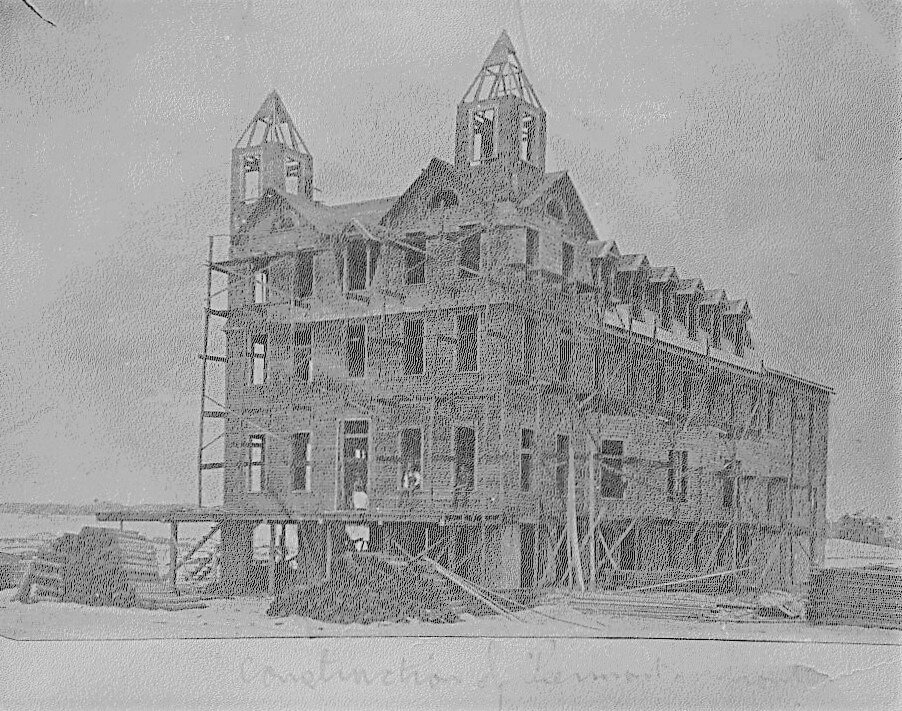

It was a wide, three-story wooden Victorian structure right on the beach, with a wrap-around porch to catch cool ocean breezes and two tall widow’s peaks, where one could look for miles at the dunes and forest of undeveloped Avalon.

Erected between what is now 33rd and 34th streets, the Hotel Peermont was built quickly in the summer of 1889, and attracted vacationers from Philadelphia, who were drawn to its claims of an “unobstructed ocean view” and escape from the sweltering heat in the city.

Early photos show men in suits and derbies and women in long dresses and fancy hats sitting on rocking chairs on the large porch, enjoying not only the sound of gulls and crashing of waves from the nearby Atlantic, but also each other’s company.

The Hotel Peermont was the second hotel built on the undeveloped beachfront, the first being the Hotel Avalon near Townsends Inlet in 1888.

That same year, the Avalon Beach Improvement Company (ABICO), whose president was George J. Rummel of Philadelphia, purchased 3,000 lots from Joseph Wells, one of the first developers of the barrier island, for about $75,000. Rummel’s first major project was to be the construction of a hotel, which he christened the “Peermont.” The origins of the name Peermont are not known, but it was widely used. In those days, the part of the island from Townsends Inlet to 25th Street was called Avalon, and from 25th to 37th streets called Peermont. There was also a wharf at the end of 25th Street, a casino, train station, volunteer fire company, and even a sailboat that bore the Peermont name.

In April 1889, a contract was signed with Francis K. Duke, a Cape May builder, to build the Peermont Hotel at a cost of $12,453, on a tract that was 220 feet by 360 feet. Its main entrance was to be on 34th Street, while a pavilion and bath houses were near 33rd Street, on the beach.

Construction began May 1, 1889, coinciding with the completion of a railroad bridge. A Cape May brickwork company was chosen for the hotel, and bricks were brought in by schooner. In the meantime, Rummel was busy with other projects in Peermont: laying out new streets, grading lots, and clearing away trees and underbrush. It was reported he sold $2,000 worth of lots on one day in mid-May.

Work was proceeding at a rapid pace on the Hotel Peermont. By May 29, the structure had been raised and weather boarding applied. Incredibly, on July 16, it opened for business fully furnished and staffed, only 2½ months from the time construction started.

The manager of the Peermont for that first season was Col. Henry W. Sawyer, a Civil War hero who previously managed the renowned Chalfonte Hotel in Cape May.

When the Hotel Peermont opened, the Peermont Station was ready for rail service from Philadelphia, which ran to 35th Street. A boardwalk was constructed, starting in front of the hotel and extending south.

By all accounts, the Hotel Peermont was considered a first-class establishment and vacationers filled its rooms. A notice in the Cape May Wave of July 20, 1889 reported:

“Accommodations are provided for 100 guests. Terms, $2.50 per day, special and reasonable rates by the week or longer periods. Situated as it is, directly on the beach and within one block from the passenger station, the location of the Hotel is unsurpassed for convenience and enjoyment.

“The house enters upon this its first season under peculiarly favorable circumstances. The building is fresh from the hands of the builders, and is newly furnished throughout in the most elegant and comfortable manner.”

Two weeks later, the Wave noted that the Peermont was now lighted by gas, and its porches would be enclosed with glass and heated by steam, to make it a first-class winter hotel, as well.

Almost from the beginning, the Peermont was plagued by erosion. Jetties were built in order to prevent the sand from shifting underneath the structures, as well as a seawall. But in September 1889, a huge storm washed out the railroad bridge, curtailing rail service for a time, and demolished the Peermont’s pavilion and bath houses, which were eventually rebuilt. The boardwalk was also a casualty of the storm.

Yet, guests continue to flock to the Hotel Peermont, no matter the season. And the Peermont was the nucleus around which community activity took place. On April 16, 1890, the Wave noted “Wild cats in the Seven Mile Beach forest are getting scarcer. Peermont Hotel was full to its capacity on Saturday.”

The local newspaper, The Round Table, which was founded by the Rev. Charles H. Bond (credited with giving Avalon its name), stated in its July 1890 edition that “The daily registers of Hotel Avalon and Hotel Peermont will show that the attractions of this lovely resort are not unheeded. Secure your rooms at once, as the hotels are not very large and when the last key goes off the board, there may be weeping and gnashing of teeth. This is a good seashore summer, for the hot waves are rolling over the land.”

In spite of the erosion problems, in April 1891 the firm of Sharp and Reeves was commissioned to build another boardwalk along the beachfront, again extending south and beginning in front of the Hotel Peermont. The boardwalk was only slightly raised from beach level, as was the previous one.

“The hotel is doing a thriving business under the management of Col. C.L. Pearce,” wrote the Star of the Cape on June 26, 1891. “Bathing season opened in June and the hotel has 30-40 guests. Fishing seems to be good, also soft crab, as for strawberries there is not a summer resort along the coast that can equal Avalon for wild strawberries and flowers. The soil is naturally good for farming.

“A bridge was being constructed across the inlet and soon will be ready for the crossing of trains,” it continued.

“It has been three years since the incorporation of the Seven Mile Beach Company, and while much improvement has been made, the destruction of the Townsends Inlet railroad bridge has twice greatly interfered with its progress, but now a superb iron structure is being substituted, to be completed by the end of summer, 1891.”

But while the Peermont Hotel, the sole asset of the Avalon Beach Hotel Company, enjoyed a robust business, Rummel soon found himself in trouble. The hotel had been financed in 1889 by a mortgage for $8,000 granted by ABICO itself, due any time within five years, with interest at 6 percent due semiannually. By May 1892, with the principal not yet due, the Hotel Company, failing to even meet its interest payments, found itself in default. ABICO filed suit, and on

May 20, 1892, a sheriff’s sale was held at the hotel, at which ABICO itself bought the hotel for $7,500.

The Hotel Peermont, once a destination for heat-weary city residents, existed only for seven years. Opened in 1889, it was destroyed by fire in 1896.